THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN UNDER THE NIGERIAN CONSTITUTION: A COMPREHENSIVE ANALYSIS

Introduction

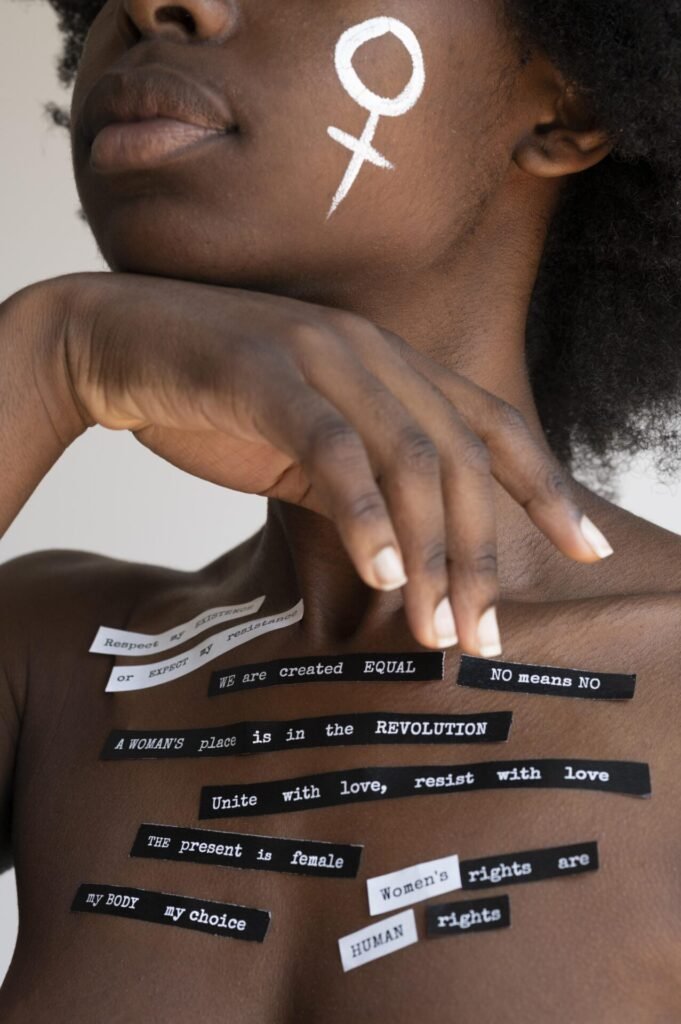

The concept of human rights is universally recognized as inherent to all individuals, irrespective of gender, race, religion, or any other status. In Nigeria, the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended), serves as the supreme law of the land, purporting to guarantee fundamental rights and freedoms to all its citizens. While on the surface, the Constitution appears to champion equality, a deeper dive reveals nuances, challenges, and outright discriminatory provisions that disproportionately affect women. This comprehensive analysis aims to dissect the various rights accorded to women under the Nigerian Constitution, highlighting both the progressive aspects and the persistent limitations, while also exploring the socio-cultural, religious, and legal factors that impede their full realization.

Chapter 1: Foundations of Equality and Non-Discrimination

The bedrock of women’s rights in Nigeria, as in many constitutional democracies, lies in the principles of equality and non-discrimination. The Nigerian Constitution, in various sections, attempts to enshrine these principles, albeit with significant caveats.

1.1 The Preamble and Fundamental Objectives

The Preamble to the 1999 Constitution sets the tone, stating the commitment of the Nigerian people to “promote the good government and welfare of all persons in our country, on the principles of freedom, equality and justice.” This foundational statement inherently includes women, suggesting a constitutional aspiration for a just and equitable society for all.

Furthermore, Chapter II of the Constitution, titled “Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy,” outlines the socio-economic, political, and cultural aspirations of the nation. While these provisions are non-justiciable (meaning they cannot be directly enforced by courts), they serve as a guide for legislative and executive actions.

- Section 15(2) states that “the State shall foster a feeling of belonging and of involvement among the various peoples of the Federation, to the end that loyalty to the nation shall override sectional loyalties.” Although not explicitly gender-specific, this provision, by promoting a sense of belonging for “all peoples,” indirectly supports the inclusion of women.

- Section 17(2)(a) and (b) declares that “every citizen shall have equality of rights, obligations and opportunities before the law” and that “the sanctity of the human person shall be recognised and human dignity shall be maintained and enhanced.” These broad statements are crucial for advocating for women’s dignity and equal standing.

- Section 17(3)(e) is particularly significant, stipulating that the State shall direct its policy towards ensuring that “there is equal pay for equal work without discrimination on account of sex, or on any other ground whatsoever.” This is a direct constitutional recognition of the right to equal pay, a vital economic right for women.

1.2 The Non-Discrimination Clause: Section 42

The most direct constitutional provision prohibiting discrimination is Section 42(1) of Chapter IV (Fundamental Rights), which states:

- “A citizen of Nigeria of a particular community, ethnic group, place of origin, sex, religion or political opinion shall not, by reason only that he is such a person—1

- (a) be subjected either expressly by, or in the practical application of, any law in force in Nigeria or any executive or administrative action of2 the government to disabilities or restrictions to which citizens of Nigeria of other communities, ethnic groups, places of origin, sex, religions or political opinions are not made subject; or

- (b) be accorded either expressly by, or in the practical application of, any law in force in Nigeria or any such executive or administrative action any privilege or advantage that is not accorded to citizens of Nigeria of other communities, ethnic groups, places of origin, sex, religions or political opinions.”

This section unequivocally prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex. It is a powerful tool for challenging laws, policies, and practices that treat women unfairly. However, the interpretation and application of this section have been a source of contention, particularly when it clashes with customary laws and religious practices, which often embody patriarchal norms.

Chapter 2: Specific Fundamental Rights and Their Application to Women

Beyond the general non-discrimination clause, the Nigerian Constitution guarantees a range of fundamental rights to all citizens, including women.

2.1 Right to Life (Section 33)

Section 33 guarantees every person the right to life. This right is fundamental and applies equally to women. It extends to protection from violence, including gender-based violence, domestic abuse, and harmful traditional practices such as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and honour killings. While the Constitution provides this fundamental right, the enforcement mechanisms and societal realities often fall short, leaving many women vulnerable.

2.2 Right to Dignity of Human Person (Section 34)

Section 34 guarantees respect for the dignity of the human person, prohibiting torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, and slavery or servitude. This right is crucial for women, as it directly addresses issues like sexual exploitation, trafficking, forced labor, and widowhood practices that often strip women of their dignity. The constitutional provision underpins the need for laws and policies that protect women from all forms of indignity and abuse.

2.3 Right to Personal Liberty (Section 35)

Section 35 guarantees every person the right to personal liberty, ensuring freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention. This right is vital for women who may be subjected to unlawful confinement, forced marriages, or restrictions on their movement by family members or communities.

2.4 Right to Fair Hearing (Section 36)

Section 36 provides for the right to a fair hearing in judicial and quasi-judicial proceedings. This ensures that women have equal access to justice, the right to legal representation, and the opportunity to present their case without bias. This is particularly important in cases of divorce, child custody, inheritance, and criminal matters where women’s voices might otherwise be marginalized.

2.5 Right to Private and Family Life (Section 37)

Section 37 guarantees the right to private and family life. For women, this includes the right to make decisions about their bodies, reproductive health, and family planning without undue interference. However, cultural and religious norms often infringe upon these rights, particularly concerning reproductive autonomy and marital choices.

2.6 Freedom of Thought, Conscience, and Religion (Section 38)

Section 38 guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. Women have the right to choose their religion, practice it freely, and change their religious beliefs. While this right is universal, its practical application can be complex for women within religious communities that impose specific dress codes, social restrictions, or limit their participation in religious leadership.

2.7 Freedom of Expression and the Press (Section 39)

Section 39 guarantees freedom of expression, including freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart ideas and information without interference. This right enables women to voice their concerns, advocate for their rights, and participate in public discourse. It is crucial for women’s rights activists and organizations to campaign against discrimination and violence.

2.8 Right to Peaceful Assembly and Association (Section 40)

Section 40 guarantees the right to peaceful assembly and association. This empowers women to form or join groups, associations, and political parties to collectively pursue their interests and advocate for change. This right is foundational for women’s movements and their ability to organize and mobilize for gender equality.

2.9 Freedom of Movement and Residence (Section 41)

Section 41 guarantees freedom of movement and residence within Nigeria. Women have the right to live anywhere in Nigeria and to move freely. This is significant in challenging cultural practices that restrict women’s mobility, particularly after marriage or widowhood.

2.10 Right to Acquire and Own Immovable Property (Section 43)

Section 43 provides that every citizen of Nigeria shall have the right to acquire and own immovable property anywhere in Nigeria. This is a critical right for women, who historically have been denied land and property ownership due to patriarchal inheritance laws and customs. While the Constitution guarantees this right, customary laws often continue to disinherit women, especially widows, posing a significant challenge to its realization.

2.11 Right to Participate in Political Activities (Sections 65, 106, 131, 177)

The Constitution implicitly guarantees women the right to vote and be voted for, by not creating any gender-based restrictions. Sections 65, 106, 131, and 177, which set out qualifications for election to legislative and executive offices, do not discriminate on the basis of sex. This ensures that women have the constitutional right to participate fully in the political process, as voters, candidates, and officeholders. However, socio-cultural barriers, economic disempowerment, and political violence often hinder women’s meaningful participation

Chapter 3: Specific Areas of Constitutional Provision and Challenges

While Chapter IV outlines general fundamental rights, other parts of the Constitution contain provisions that either support or, in some cases, undermine women’s rights specifically.

3.1 Citizenship Rights (Sections 25, 26, 29)

The provisions on citizenship present a complex picture for women:

- Citizenship by Birth (Section 25): This section generally provides for equal citizenship by birth for both men and women.

- Citizenship by Registration (Section 26): This is where a significant discriminatory provision lies. Section 26(2)(a) states that “any woman who is or has been married to a citizen of Nigeria” can be registered as a citizen. This provision facilitates citizenship for foreign women married to Nigerian men. However, there is no reciprocal provision allowing foreign men married to Nigerian women to acquire Nigerian citizenship by registration. This unequal treatment has been a major point of advocacy for women’s rights groups, as it undermines the equality enshrined in Section 42.

- Renunciation of Citizenship and “Full Age” (Section 29): While Section 29(4)(a) defines “full age” as eighteen years and above, Section 29(4)(b) states that “any woman who is married shall be deemed to be of full age.” This seemingly innocuous provision has been widely criticized for indirectly legitimizing child marriage, as it implies that a girl, regardless of her chronological age, is considered an adult upon marriage. This has severe implications for the education, health, and overall development of young girls.

3.2 Right to Education (Section 18)

Section 18 of the Constitution, under the Fundamental Objectives, states that the government shall direct its policy towards ensuring equal and adequate educational opportunities at all levels. While not gender-specific, this provision is crucial for women’s advancement. The State is enjoined to provide free, compulsory, and universal primary education, and promote science and technology. Despite this, girls in many parts of Nigeria, particularly in the North, face significant barriers to education due to cultural norms, poverty, and insecurity.

3.3 Right to Health (Section 17)

While there is no explicit “right to health” in Chapter IV, Section 17(3)(d) of the Fundamental Objectives states that the State shall direct its policy towards ensuring that “there are adequate medical and health facilities for all persons.” This indirectly supports women’s access to healthcare, including maternal health services, reproductive health, and protection from diseases. However, the non-justiciable nature of this provision means that its enforcement depends largely on government policy and resource allocation.

3.4 Right to Work and Social Welfare (Section 17)

Section 17(3)(a), (b), (c), and (e) collectively address the right to work and social welfare, emphasizing opportunities for livelihood, just and humane conditions of work, safeguarding of health and safety, and equal pay for equal work. These provisions are critical for women’s economic empowerment and protection in the workplace. Yet, challenges persist, including gender-based discrimination in hiring and promotion, unequal pay, and inadequate maternity protection.

Chapter 4: Interplay with Other Legal Frameworks and International Instruments

The Nigerian Constitution does not exist in a vacuum. Its interpretation and application are often influenced by other legal frameworks, both domestic and international.

4.1 Customary and Religious Laws

One of the most significant challenges to the full realization of women’s rights under the Nigerian Constitution stems from the parallel existence and application of customary laws and religious laws (especially Islamic law in the Northern states). These legal systems, which govern personal and family matters for a significant portion of the population, often contain provisions that are discriminatory against women, particularly in areas like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and child custody.

For example, customary laws frequently deny women land inheritance rights, favour male children, and permit practices like forced widowhood rites. While the Constitution is supreme, courts often face a dilemma when constitutional provisions clash with deeply entrenched customary or religious practices. Some judicial pronouncements have indeed declared certain customs contrary to “natural justice, equity, and good conscience,” aligning with constitutional principles. However, the application remains inconsistent, and societal adherence to these practices remains strong.

4.2 International Human Rights Instruments

Nigeria is a signatory to several international human rights instruments that protect women’s rights, including:

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW): Nigeria signed CEDAW in 1984 and ratified it without reservation in 1985. CEDAW is often referred to as the international bill of rights for women, obliging states to eliminate discrimination in all forms and spheres of life.

- The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol): Nigeria ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2004. This protocol addresses a wide range of women’s rights, including the right to dignity, life, integrity, and security of the person, elimination of discrimination, elimination of harmful practices, reproductive health rights, and economic and social welfare rights.

While Nigeria’s ratification of these treaties signifies a commitment to gender equality, the challenge lies in their domestication. For an international treaty to have the force of law in Nigeria, it must be enacted into domestic legislation by the National Assembly. Many key provisions of CEDAW and the Maputo Protocol have not been fully domesticated, creating a gap between international obligations and national enforceability. However, Nigerian courts have, on occasion, referred to these international instruments in their judgments, signifying a growing recognition of their importance.

4.3 Domestic Legislation

Several domestic laws have been enacted to further protect women’s rights, some of which complement the constitutional provisions. These include:

- The Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act (VAPP Act) 2015: This landmark legislation aims to eliminate violence in private and public life, prohibiting various forms of violence against persons, including women, such as FGM, forced marriage, domestic violence, and sexual violence. The VAPP Act has been adopted by some states, but not all, limiting its nationwide impact.

- Child Rights Act 2003: This Act domesticates the Convention on the Rights of the Child and seeks to protect children (including the girl-child) from abuse, exploitation, and discrimination. Its provisions on the minimum age for marriage are crucial in countering the implications of Section 29(4)(b) of the Constitution.

- Labour Act: While the Labour Act contains some provisions for maternity leave, it also has discriminatory sections, such as prohibiting women from night work in certain industries, which has been criticized as outdated.

Chapter 5: Limitations, Challenges, and Enforcement Mechanisms

Despite the constitutional guarantees and other legal frameworks, several limitations and challenges impede the full realization of women’s rights in Nigeria.

5.1 Constitutional Gaps and Ambiguities

As highlighted, certain constitutional provisions, particularly Section 29(4)(b) on “full age” and Section 26 on citizenship by registration, directly or indirectly create loopholes for discrimination against women. The generally male-centric language used in some parts of the Constitution (e.g., using “he” when referring to a citizen) also subtly reinforces patriarchal norms, though efforts are being made to advocate for gender-neutral language in constitutional reviews.

5.2 Socio-Cultural and Religious Barriers

Deep-seated patriarchal traditions, harmful cultural practices, and restrictive interpretations of religious texts continue to be major impediments. These informal systems often override constitutional provisions in people’s daily lives, leading to:

- Gender-Based Violence: High prevalence of domestic violence, sexual assault, FGM, and other forms of violence against women, often perpetuated with impunity due to societal acceptance or inadequate enforcement of laws.

- Discriminatory Inheritance Practices: Women are frequently denied inheritance rights to land and property, especially in rural areas, leading to economic disempowerment.

- Limited Access to Education: Cultural preferences for educating boys over girls, early marriage, and insecurity (e.g., Boko Haram insurgency targeting girls’ education) continue to limit girls’ access to and retention in schools.

- Political Underrepresentation: Despite constitutional rights, women remain significantly underrepresented in elective and appointive positions across all levels of government due to cultural barriers, economic disadvantages, and political structures.

5.3 Economic Disempowerment

Poverty disproportionately affects women, limiting their access to legal services, education, healthcare, and economic opportunities. This economic vulnerability often makes it difficult for women to assert their rights, leaving them dependent and susceptible to abuse.

5.4 Weak Enforcement Mechanisms and Access to Justice

Even where laws exist, their enforcement is often weak due to:

- Corruption: Corruption within the law enforcement and judicial systems can undermine justice for women.

- Lack of Awareness: Many women are unaware of their constitutional and legal rights due to low literacy rates and limited access to information.

- Slow Judicial Process: The lengthy and expensive nature of litigation can deter women from seeking legal redress.

- Societal Pressure: Women often face immense family and community pressure to not report abuses or to withdraw cases, especially in matters involving family members.

- Inadequate Institutions: Insufficient funding and capacity of institutions responsible for protecting women’s rights, such as the police, courts, and human rights commissions.

5.5 Institutional and Systemic Biases

The legal and justice systems, including law enforcement, often reflect societal biases. This can manifest in how cases of gender-based violence are handled, the attitudes of judicial officers, and the overall lack of gender sensitivity in legal processes.

Chapter 6: Advocacy, Reforms, and the Way Forward

Despite the formidable challenges, there have been consistent efforts by women’s rights organizations, civil society groups, and progressive individuals to advocate for constitutional and legal reforms, and to push for better enforcement of existing rights.

6.1 Constitutional Reforms

Ongoing constitutional review processes provide opportunities to address discriminatory provisions. Key demands include:

- Amendment of Section 26(2) on Citizenship: To grant Nigerian women the same right as men to confer citizenship on their foreign spouses.

- Amendment of Section 29(4)(b) on “Full Age”: To remove the clause that deems a married woman to be of full age, irrespective of her actual age, thereby clearly prohibiting child marriage.

- Inclusion of Gender-Neutral Language: To replace gender-specific pronouns with inclusive language throughout the Constitution.

- Domestication of International Treaties: Ensuring that CEDAW and the Maputo Protocol are fully domesticated and enforceable in Nigerian courts.

6.2 Legislative Advocacy

Continued advocacy for the enactment of comprehensive laws that protect women’s rights and criminalize harmful practices, such as stronger anti-FGM laws, marital rape laws, and more robust protection against domestic violence, is crucial. The wider adoption and effective implementation of the VAPP Act across all states are paramount.

6.3 Judicial Activism

Courts have a critical role to play in interpreting constitutional provisions in a manner that upholds gender equality and human rights. Encouraging judicial officers to be gender-sensitive and to refer to international human rights standards where domestic law is silent or ambiguous can significantly advance women’s rights.

6.4 Public Awareness and Education

Massive public awareness campaigns are needed to educate women about their rights and to sensitize the general populace, community leaders, and religious institutions about the importance of gender equality. This includes challenging harmful stereotypes and cultural norms through education and dialogue.

6.5 Empowerment Programs

Economic empowerment initiatives for women, including access to credit, vocational training, and property ownership, are essential to enhance their ability to assert their rights and escape cycles of dependence and abuse.

6.6 Strengthening Institutions

Building the capacity of law enforcement agencies, the judiciary, and human rights institutions to effectively respond to and prosecute cases of violence and discrimination against women is vital. This includes gender sensitivity training for police officers, lawyers, and judges.

6.7 Data Collection and Research

Reliable data on the prevalence of gender-based violence and discrimination is crucial for informing policy and legislative interventions. Supporting research and data collection initiatives can provide evidence-based insights for advocacy.

Conclusion

The Nigerian Constitution, while affirming fundamental human rights and explicitly prohibiting sex-based discrimination in Section 42, presents a mixed bag for women. It lays a foundational framework for equality but is riddled with certain problematic provisions and faces formidable challenges from deeply entrenched socio-cultural and religious norms. The gap between constitutional ideals and lived realities for many Nigerian women remains significant.

Achieving true gender equality in Nigeria requires a multi-pronged approach: sustained constitutional and legal reforms, robust domestication of international human rights treaties, proactive judicial interpretation, effective law enforcement, and widespread public education. Ultimately, the full realization of women’s rights is not merely a matter of legal provision but a societal transformation that recognizes women as equal partners in national development, ensuring their dignity, autonomy, and well-being are respected and protected under the supreme law of the land. The journey towards a truly egalitarian society, where every Nigerian woman can fully enjoy the rights enshrined in the Constitution, continues, demanding unwavering commitment and collective action from all stakeholders.